The clock on the wall indicated it was 3 pm—unable to see the position of the sun through the pollution that muddied the sky, I had no choice but to trust it. I was in Jiayuguan, one of many places in Gansu province where the Great Wall was said to end, though the L-shaped apartment block I’d ducked inside could’ve been anywhere on the Chinese mainland, all 3.7 million square miles of it.

As the waitress walked away, having jotted down my order for the only recognizable item on the restaurant’s menu, one of the the four middle-aged men with whom I’d been trying to avoid eye contact shouted out to me.

“Ni yao he ma?” He asked, oscillating between slur and staccato, and held up an overflowing shot glass.

I smiled and declined politely, hoping he’d dive back into whatever shit he’d been shooting with his three friends. But instead he stood up, walked over to my table and plopped down directly in front of me. He dinged the vessel playfully in front of me, and rephrased his question as a statement. “Ni xiang he jiu.”

I didn’t want to take even a sip of the spirit, of course; it was quite clearly moonshine, in spite of the semi-professional label on its bottle. Still, I was unprepared for the magnitude of the disgust I’d feel as it sloshed along my taste buds, like a garrison at one of the forts that used to surround this city realizing it was 10 feet too short the moment the Mongols fired their first arrows.

My response was likewise resigned. “Xie xie,” I said, pushing the receptacle as far away from me as my arm could politely stretch.

My new acquaintance remained for a moment, speaking in rapid-fire Mandarin, either unaware of how poor my skills were or as a means of mocking them. He eventually got the message, however, and retreated to his own platoon.

I did consider for a moment (and only one—a steaming plate of gong bao ji ding appeared in front of me the very next instant) that my behavior might’ve been rude or even unkind. But I had no other choice. Odd as it might sound, solitude was the best antidote to the deprivation that would come to define my time in China’s Wild West.

Deprivation in a literal sense, yes. I went nearly two weeks without clean air, coffee, the sound of confidently-spoken English, sex, fast (and free) internet, voluptuous trees, comedy, washing machines or seeing a single naturally-occurring body of water. Retreating into myself, where I could synthesize the neural responses all these creature comforts would’ve produced, was nothing if not a preservation method.

But my trip also spoke to a more esoteric trend line I’ve plotted through my recent past, which visualizes the increasingly negative correlation between my raw enjoyment of a place and the intrinsic value of the conclusions being there allows me to draw.

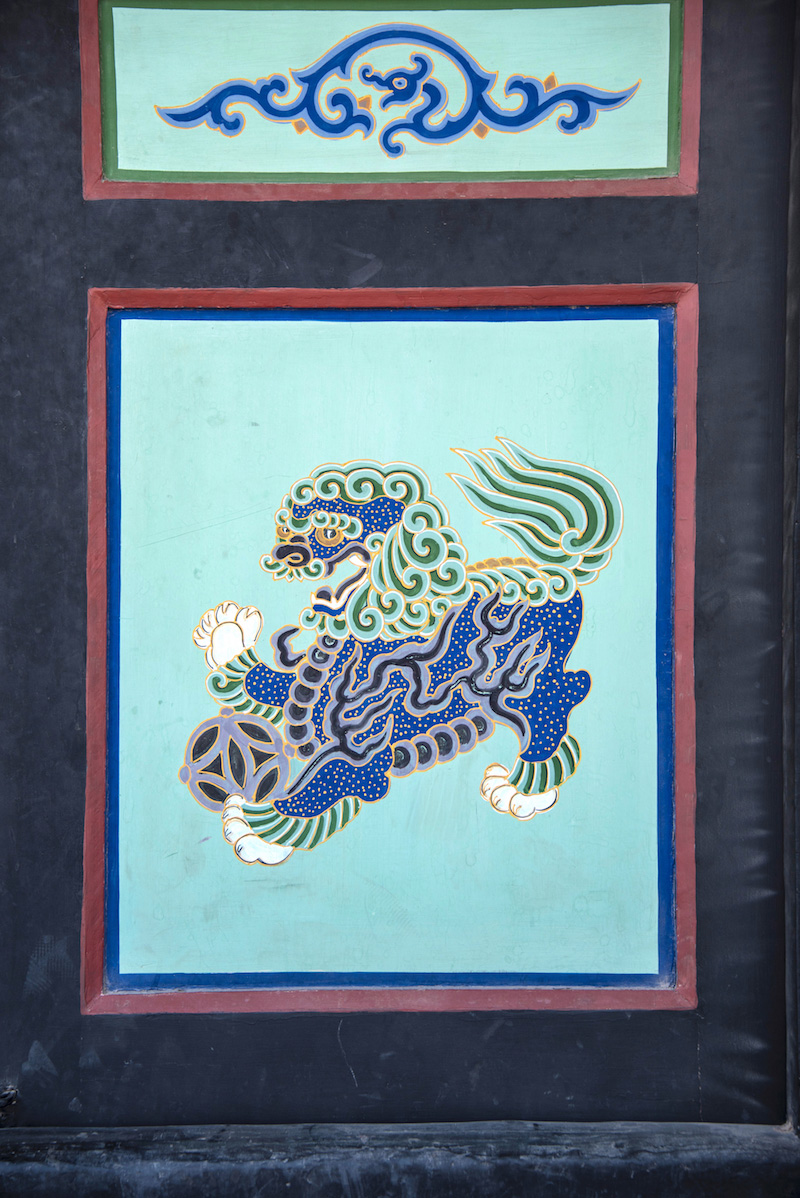

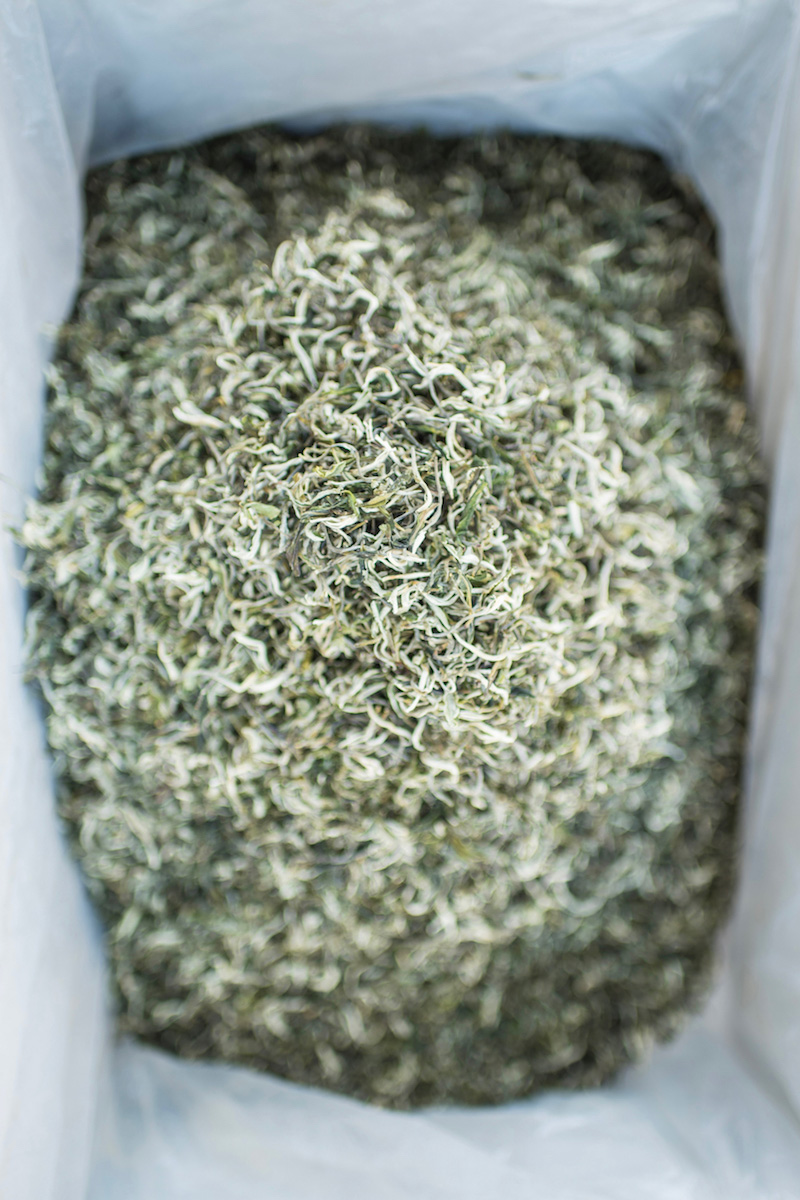

I’m not ashamed to say that Starbucks was my first stop arriving back in Xi’an at the conclusion of my Gansu trip, or I opened Grindr before I even pressed the keycard to the door of my junior suite. Yet in spite of the sheer pleasure I felt upon returning, more or less, to civilization, I will happily deprive myself as often as possible if I’m able to continue creating sustenance like the sort that emanates from the photos you see below.