“That sounds like it’s in Tibet,” the immigration officer at Tianfu Airport laughed, when I told him the name of my hotel in Chengdu. Which was ironic, considering I had ultimately opted to spend a night in the Panda City because I couldn’t get a flight to Lhasa the same day.

I responded with a smile, but without words; he stamped me through seconds later.

It was my first tine in mainland China since before the pandemic, and some things had changed dramatically. Among them, the taxi driver using AI to direct him to my hotel near the city’s Wenshu Monastery.

Others had not. The driver couldn’t manage to find the right location in spite of me giving him a Chinese name and address. Once I arrived at the hotel, staff initially told me it had thrown out my Tibet travel permit, in spite of the document being safe in an envelope literally under the right hand of the receptionist.

“Bu hao yi-si,” she apologized, in spite of an expression on her face that was anything but contrite, her breath redolent with the whole-leaf tea she was sipping out her thermos. I walked through the hotel’s courtyard, where its namesake Buddha sat, and up to my room.

Not much daylight remained, a truth the infamous sea of clouds in which Chengdu tends to swim made even more acute. I made a beeline for Jin Li Street, in particular one huge ginkgo whose branches had more “lucky packets” tied to them than tree stuff, but night had fallen by the time I got there.

The bulbs beneath its canopy made the remaining leaves (which were at least a week away from their autumn peak) seems a shade or two more golden.

Later in the evening, looking down the Jin River at lit-up Anshun Bridge and its mirror-image reflection in the glassy waters, a strange sense of peace came over me. It belied the dozens (if not hundreds) of other people enjoying the same view as me, most of them distant in their disposition from the tranquility of the scene.

It was peace, and not just relief or resignation; it was a profound sort of peace, the sort you later tell someone let you that know you were in the right place at the right time.

The next morning, at Chengdu’s other airport, neither check-in nor security staff gave more than a cursory glance to the permit whose seeming disappearance less than 24-hours earlier had seemed nothing short of an apocalypse.

In fact, apart from a disproportionate number of passengers spinning handheld prayer wheels and speaking Tibetan, this could’ve been any other domestic Chinese flight.

Well, at least until take-off. Less than 15 minutes after that, we were not only far above Chengdu’s infamous mist; the urban lowlands that extend so far in every direction from the city center seemed like they must’ve been on another planet, as we flew first over snow-capped peaks nearly as high in altitude as the Airbus A330, and then above the eastern reaches of the Tibetan Plateau, which was even higher than those.

As the plane landed at Gonggar Airport, to be sure, the ash and birch trees (there were no obvious ginkgoes here) were perfectly yellow. At ground level what seemed like seconds later, onboard a tourist van speeding toward the city center, the contrast of the citrine leaves with the majorelle sky seemed almost precise, as if the two shades sat directly across the color wheel from one another.

Months ago when it was just a plan, the circumstances of my travel—foreigners can only enter Tibet following the purchase of an organized tour—disappointed me. But as I chatted with an American, an Australian and an Austrian, I felt humbled.

“I’m onboard a vehicle I’m not driving bound for a hotel I didn’t have to book myself,” I admitted, when the American asked me whether I was excited about the tour. “It’s nice to be proceeding mindlessly for once.”

After checking in, I made my way toward famous Potala Palace, which was even more striking in-person than it had been in pictures. And not just because its white-and-burgundy facade seemed to sit at the midpoint between the yellow of the ash and birch framing it, and the blue sky into which it rose.

No, I told the Austrian, whom I’d run into by chance and who only ended up walking with me for a few minutes before going on his own way, Lhasa would look the same as any other nondescript city in Western China, were it not for this structure.

I wasn’t sure if he caught the ironic subtext of what I was saying; his English was excellent, but it wasn’t his first language. Anyway, I didn’t dare explain myself further.

In the short time we walked together, we had to pass through security checkpoints at least three times: Twice to cross two streets; and another time to access the plaza in front of the palace. It seemed at least two more would’ve been required to go inside, which we of course couldn’t do without our guide, whom we hadn’t even met yet.

Most of the other people passing through the x-ray machines were ethnic Tibetans, placing their prayer wheels and beads into plastic bins as they passed through facial recognition turnstiles, which didn’t work for our white faces but recognized each local person immediately.

Clearing the final checkpoint, I censored even my own thoughts; it didn’t feel sufficient simply not to speak out loud what I was feeling. The locals, for their part, made their way up the palace’s stairs and toward its chapels as if nothing insidious was at hand, seemingly oblivious to the towering portraits (on one side Xi Jinping; on the other the rest of modern China’s presidents) smiling slyly from ground level.

The Austrian, for his part, couldn’t have been more than 25 years old—he must’ve been an infant when the movement to “Free Tibet” stopped being fashionable.

If there’s one words that comes immediately to mind when I think of Tibet, it’s butter. Butter is everywhere here: It’s in the tea; it forms the candles that burn inside virtually every Tibetan sacred spot, whose worshippers either enter with a tub of their own butter, or buy one at the gates.

I’m sure my guide explained to me why this is, though I don’t remember being convinced that the reason she gave me was the real one.

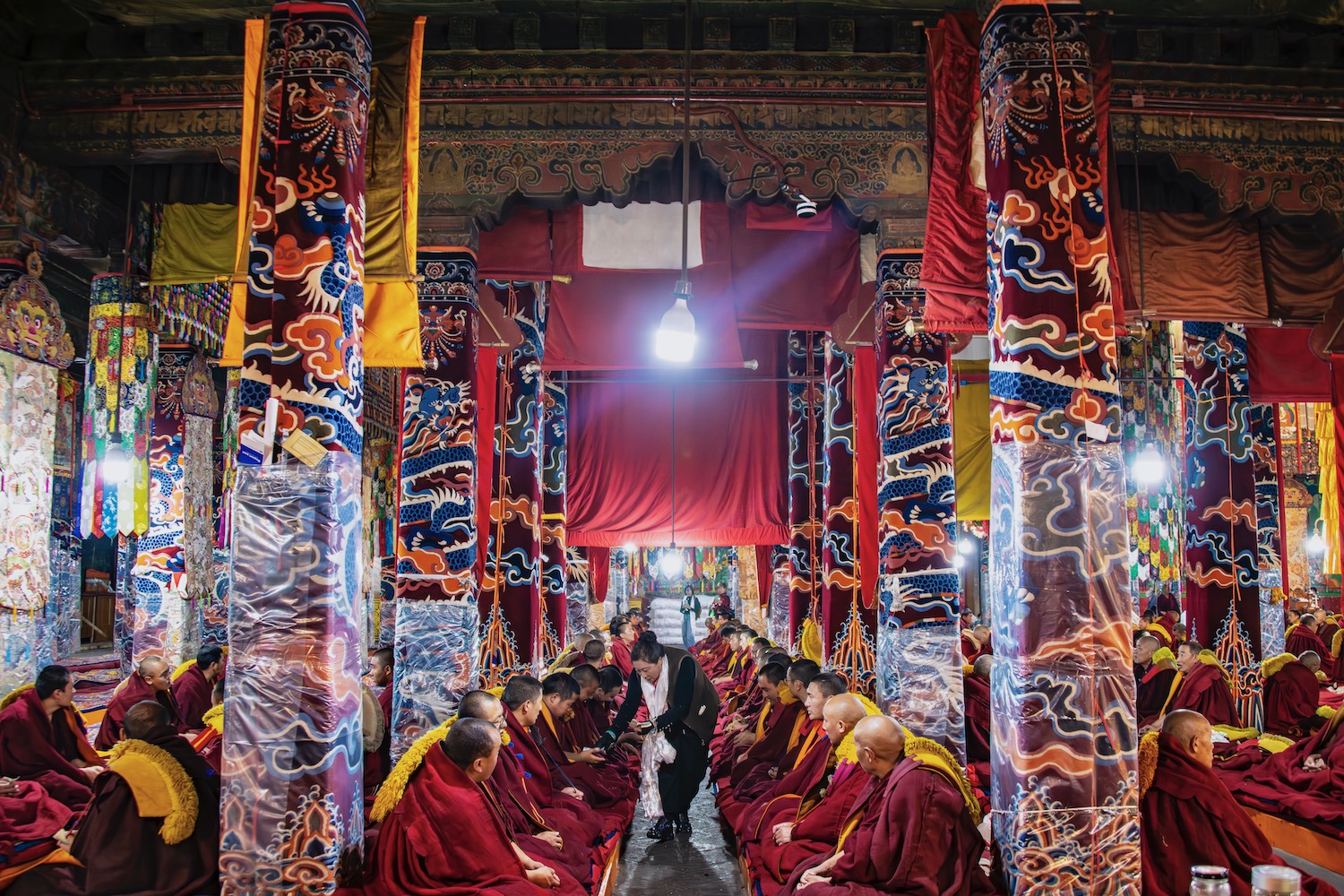

Or maybe I was just distracted. Upon entering the main hall of Drepung Monastery, after all, the throaty chanting of the monks seemed like something you might hear on Arrakis, hammering home how otherworldly Tibet already seemed, less than 24 hours after I got there.

NO PHOTOS, the placard on the wall stated, echoing the words of my guide. Not a single person in our group (or any of the other groups exploring its innards) obeyed this directive; I wasn’t about to be the odd man out.

“Did you get any good shots?” asked a French girl who hadn’t been at the airport a day earlier, behind her an ash tree contrasting perfectly with the still-blue sky.

I nodded. “I mean I think so. I haven’t scrutinized them.”

She was reluctantly eating the noodles she had enthusiastically ordered. It seems (though she didn’t say aloud) that yak meat had sounded better than it smelled or tasted. For my part I’d ordered a chicken noodle soup, though the meat didn’t really seem like chicken.

“And those aren’t noodles,” my guide—whose name I remembered, just then, was Dickey (like the pants) interjected after I told the French girl’s German boyfriend how surprising it was to be eating udon in Tibet. She declined to explain what they were, if not noodles.

We proceeded next to another monastery (Sera) where I once again ignored a prohibition on cameras. This time it made even more sense; we were watching a monk debate. If we couldn’t understand it—well, beyond how remarkable it was that debate was allowed anywhere in Tibet—the least we should be permitted to do was document it visually.

Heading next into Old Lhasa to visit Jokhang Temple, I found myself distracted by small details, in spite of how majestic the towering edifice and how brightly its golden goof gleamed in the sun. And not just the oxygen apparatuses to which the American woman and two of the five Singaporean participants who’d joined the tour were hooked up to, though those were impossible to ignore.

On the ground in front of the temple’s entrance, worshippers were performing what I can describe only as sun salutations. Well, some of them. Others were clutching beads and reading holy books; still were spinning prayer wheels or sifting colorful pebbles between their open fingers and onto golden silks, only to collect the rocks again and start the process over.

Looking up into the sky, hoping to distract myself from yet another placard that announced a camera ban, I noticed birds that appeared to be seagulls, though that couldn’t have been the case. Lhasa was farther from the ocean than almost any other city in the world; they never could’ve survived that long.

Exiting the tour bus at the hotel that night after a buffet dinner in a restaurant that could’ve been in Nepal or Bhutan, a passing garbage truck blared a MIDI version of “It’s a Small World (After All).” Overnight, I woke to what I assumed in my sleepy stupor had been an explosion, but what turned out simply to be fireworks.

If you’ve been reading this blog for a significant amount of time—nearly a decade, as crazy as it feels to say that—you might remember that I’d planned to come to Tibet in the fall of 2016. I decided, of course, to go instead to Nepal, which seemed like the right decision the moment I walked onto the streets of Kathmandu, in spite of my not having any frame of reference for what it might be like in Lhasa.

Let alone Shigatse, Tibet’s second city, which was our second stop after the capital.

Well, our second official stop. En route, Dickey told us that we would be stopping at the birch-billowed confluence of the Lhasa and Brahmaputra Rivers; we passed the intersection without any fanfare, apart from the sass I spat out when she lied to me.

“There was no place to park the bus,” she lied, in spite of the fact that at least half a dozen spots were open between the other tour buses parked there.

I might’ve stayed angry the entire day, had we not been in Tibet. But we were in Tibet, which means that Yamdrok Lake (which, up to that point, was probably the most beautiful place I had ever seen with my own eyes) was literally right down the road.

Of course, it wasn’t all prayer flags and cold, clean air. About an hour after looking down at the lake from thousands of feet up, we headed down to a village along the shore to have lunch. The meal was delicious; but as I walked down to the water to take some pictures, a local man squatted down just a few feet from me and defecated, as if I wasn’t even there.

The beauty continued shortly thereafter, thankfully, first at the the stupa beneath the behemoth Kharola Glacier, and then at Manla Reservoir, which at first glance seemed like it might’ve been even more gorgeous than Yamdrok though, looking back, I can’t say this for sure. We had just a few minutes there.

“We need to arrive in Shigatse to validate your permits within an hour,” Dickie said, explaining that if we didn’t, we might not make it to Everest Base Camp before nightfall the next day.

“How far are we?” I asked, knowing that I could trust neither Google Maps nor Apple Maps within great China, even within a VPN.

She answered succinctly “About an hour. We’ll just barely make it.”

In fact, I did open my maps apps, but not to verify the figure Dickey had given me. Rather, I wanted to get a sense of the general geography of Western Tibet. Among the facts I gleaned? I was only about 50 miles (as the crow flies) north of Bhutan, where I’d been a week earlier, even if it felt like a year had passed.

About 30 minutes from Shigatse, we passed Gyantse Dzong, which if I hadn’t been paying close attention, I might’ve assumed was a replica of Patala Palace. The fortress, Dickey explained, had been instrumental during the Qing Dynasty, when local Tibetans successfully fought off the British.

I considered, for a second, remarking about how much less successful they’d been in keeping the Chinese out. But I thought better of it at the last moment.

Heading at last into town, where of course the Chinese flags on either side of the road were made of rigid metal, and placed so close to one another that you couldn’t drive for more than a second or two without seeing one, I also noticed that pictures of President Xi were even more numerous than they’d been in Lhasa, in spite of Shigatse seeming generally less militarized.

I checked into my room at what I assume was the only three-star Western hotel in this city and then, in lieu of sitting down at one of the cookie cutter hot pot restaurants just beneath it, headed across the street to Darewa Park.

While it appeared as if fireworks were being set off, calling back to the night before in Lhasa, the spectacle was in fact a fountain being illuminated.

Although I couldn’t understand the lyrics, the music was traditionally Chinese enough that I could only assume the entire production was a sort of propaganda, a fact that absence of virtually anyone besides me seemed to hammer home.

Both the sound and color came to an abrupt stop what seemed like moments after I arrived, which left me alone with my thoughts.

Could a Tibetan nation, I wondered, even stand on its own?

Beautiful nature is priceless, declared the English writing of the road sign we passed on our way to Everest Base Camp the next morning. I wondered what the Chinese and Tibetan texts directly translated to, but not enough to photograph them and see it for myself.

Just then, Dickie’s ringtone (a helium-voiced, vocoded version of Adele’s “Easy On Me”) being blasting through her phone. But I was too distracted by the foreboding clouds in the distance to care much about what she might’ve been saying, or to whom.

My mood, to be sure, darkened along with the sky.

“It’s crazy,” I said, while waiting for my food at a smoky Sichuan restaurant about halfway between the city and Rongbuk Monastery, the closest place to Chomolungma, as it’s known in Tibetan. “The Chinese brought high-speed rail, high-speed internet and modern roads out here,” I continued ranting. “But not modern plumbing.”

(I may or may not have relieved myself at a filthy squat toilet immediately prior to sitting down at a lazy Susan table with the German, the Frenchwoman, the Aussie and an American couple who, up until that point, had hardly said a word to me.)

The restaurant writ-large was less than clean, a fact that smoke wafting through the dining room (our table was the only one where not a single person was lighting up) hammered home.

My mood was dark, to the extent that I shot down the Aussie when we arrived about an hour later at a viewpoint where we would’ve been able to see the five highest mountains in the world, had they not all been obscured by clouds.

“We don’t need to stop here,” I said callously, not to her but so that she could hear it, in spite of how eager she seemed to photograph the horizon. “There’s nothing to see.”

She was defiant. “This is everything to me,” she said, and continued shooting. In hindsight I’m glad she did, though in the moment her apparent optimism annoyed me.

As we got back in the bus and headed down to a transit depot, where a public vehicle took us the rest of the way to where we’d be saying, I became downright embittered. This in spite of the fact that people huffing oxygen sounded legitimately like Darth Vader, which made me laugh in spite of how pissed off I was.

So thick were the clouds at this point that Everest was totally invisible. Worse, the forecast for the next day revealed that we could expect very similar weather, with heavy snow set to fall no less.

But not the day after that, or the day after that, or the day after that. We would literally be there on the two worst days of November, the only two cloudy days of the dry season.

Thankfully, the German and the Frenchwoman inspired me to spend the evening not wrought with anxiety over whether we’d be able to see Everest the next morning, but instead eating, drinking and doing our best to be merry.

Everest Base Camp, I reminded myself as the German poured Lhasa beer into my glass what felt like 100 times, is more about camp that it is about the being at the base of Everest.

The next morning at breakfast, however, my cynicism returned. As far as I could tell out my window at breakfast, we wouldn’t be seeing the mountain then either.

Just then, however, the peak began peeking through. “I think we need to move,” the Frenchwoman said, as if she was giving marching orders. And so we set out.

Confronted with hope of seeing what we came for for the first time since arriving, it dawned on me only upon stepping out into the cold that the air here was a good 10ºC colder than it had been in Lhasa or Shigatse.

But it didn’t bother me. “This isn’t much colder than my hometown in the middle of January,” I said, referring to St.Louis. “It’s worth enduring for a few minutes.”

Or 60. After all of us spent no less than an hour photographing the mountain in various states of visibility, I went into my room at the spartan hotel to pack up my things—and emerged to find literally no one there. I panicked: Had I spend longer than I thought? Had they left me at Base Camp?

Shamefully, by the time Dickey finally found me, I snapped at her harshly, in a way I don’t recall having done to anyone in almost a year, and maybe longer than that.

But instead of getting angry, she empathized with me. “You were always very happy before,” she put her arm around me, and sought with the entirety of her being to calm me instead of to scold me. “But now you are very angry.”

She then immediately began taking me on the tour I’d missed, explaining intricate details of Rongbuk, which was the world’s highest monastery. She mostly stuck to facts but, as we were leaving, noticed that my frown still wasn’t quite upside down.”

“Please feel happy again,” she insisted. “And not just for me. I have a feeling you’re going to need some happiness sooner than you think.”

Prior to leaving Shigatse two mornings later, we visited resplendent Tashi Lunpo Monastery, which might have been the architectural highlight of my trip up to that point. You know, had it not become clear as I explored that my braindead countrymen would be returning Donald Trump to the White House.

I don’t remember a lot past that point. We returned to Lhasa, where I said goodbye to the German and the Frenchwoman and most of the Singaporeans. The American couple also parted ways with us; the single American woman whom I’d met at the airport had apparently left much earlier due to severe altitude sickness.

On the penultimate day of the trip, was the day myself, the Australian and the three remaining Singaporeans would be headed to holy Namtso Lake which, if I’m honest, was most of the motivation for my trip as a whole.

The journey there, to be sure, felt like longer than it was (at 3.5 hours, it would less than half the time we needed to visit Shigatse from Lhasa, or Everest Base Camp from Shigatse).

It didn’t help that we stopped en route at a grimey gas station, where a cordyceps vendor tried to flatter me (“You’re the most handsome man I’ve ever seen,” he insisted in English) into paying ¥60 for a single desiccated caterpillar.

In the distance, I could see that the mountains were covered in the snow that had nearly ruined my time at the foot of Everest. It was only upon arriving on the shores of the lake, whose waters were so bright and blue-green that they almost seemed dyed, that I realized how much I prefer having clear skies here instead of there.

Arriving on the shores of the lake, I mounted a white yak who wanted absolutely none of my behind on his back, in spite of his owner happily charging me to be able to sit there for a few seconds while I snapped pictures of myself using my tripod.

Although I did briefly hike up to a viewpoint that offered a much better panorama of the lake, I got the shots I needed to within less than an hour of arriving on Lukang Peninsula, where most sightseeing in the Namtso area occurs.

I found Dickey, to be sure, underneath a white tent with a dozen or so other people. They were seated in groups of two or three (Dickey herself was alone) at colorful picnic tables arranged in a way that almost reminded me of a hipster farm-to-table restaurant.

“Coffee?” She asked, and busted out a Nescafe 3-in-1 she appeared to have taken from our hotel in Lhasa.

I declined, but she misunderstood me, so I graciously accepted that creamy concoction she made me in spite of my refusal. Across from us, a boy that couldn’t have been far past the age of 10 plopped down, within seconds lighting up a cigarette as if he genuinely thought doing so would impress me, rather than horrifying me.

Not that I was paying too much attention. Within minutes, Dickey had opened up to me in a way that both connected me to her emotionally in a much deeper way, but also made me think.

Obviously, given the sensitivity of basically everything about Tibet and the Tibetan people, I can’t go into too much detail about what she said, though you can click here to learn about the policy that made me so sad when Dickey talked herself out of her dream.

“I want to go to Greece one day,” she said. “I’m obsessed with it, but I don’t know if I’ll ever get there.”

She initially questioned me about my my own personal life. She was curious about my marriage and about my experience being gay in general; she then remarked that she’d rather her young daughter eventually grow up into a lesbian than ever be harmed by a man.

But she quickly and suddenly pivoted back to tour guide speak, explaining that Tibetans saw Namtso as the tears a certain goddess shed after her husband (the highest of the Nyenchen Thangla mountains in the distance) took Dorje Gegkyi Tso (the spirit of Yamdrok, which you might remember from earlier in this trip) as a mistress.

Just then, a woman slightly older than both Dickey and I approached me, with Dickey translating her words for me. “She wants to know if she can photograph her father with you,” she explained, pointing to the elderly but ebullient man walking because her with a cane that didn’t seem to slow him down much.

I put my arm around him and smiled widely, too shy to ask Dickey to facilitate an entire conversation between us. I’m sure he had stories to tell, and that he was probably candid enough after nearly a century that I could’ve gained some unforgettable insight for doing so.

Instead, I ended up taking Dickey up on her offer of a second 3-in-1, and instead sat mostly in silence as I watched and listened to the Tibetans interact with one another.

I wanted to draw a sappy conclusion. They might not have a real country or the right to leave it, I tried to rationalize the level of oppression every single person in the tent had spend their entire life living in, but at least they have community.

This, of course, was a cop out; I feel dumb for having thought of saying it at all, even for a second. It’s not unlike all the kumbaya posts that have sprung up since the election, encouraging people of my approximately political persuasion to lean on one another for the next four years, as if commiseration is any match for four years of unchecked power on the part of a former president with admitted authoritarian impulses.

But even this simile is ridiculous: Even on America’s worst day, Americans are nothing if not drowning in freedom and privilege. It’s irresponsibly so much as to speak about our seeming hardships in the same sense as the decades-long plight of Tibetans.

Who, yes, have community, but not even so much the agency to leave their home, let alone to pray in the chapels at their capital’s palace without going through at least three security checks.

As our group looked upon the harsh “sky burial” in the distance, Dickie posed a question. “Do you know why they make the children watch it?”

All of us shook our heads.

“If you’re afraid of death,” she explained, “you’ll be a good person. We try to instill this fear when people are still young.”

Certainly, all the elderly women walking clockwise around the stupas of Chimelong Nunnery seemed to be scared. They (and just about every other person I saw anywhere in Tibet) clutched their prayer beads constantly, as if doing so were the only way to stay alive.

I thought back on this moment often during the immediate week following my departure from Tibet—which, in spite of having happened after I spent a full 10 days there, felt like it came mere moments after I arrived. Perhaps that’s the main reason to fear death: Because of how quickly it comes.

Walking around Chengdu again, to be sure, during the 36 additional hours I spent there, it dawned on me that precisely 16 years had passed since the death of my childhood dog Penny, meaning she’s now been dead a full year longer than she was alive.

So too did the 15th anniversary of my move to Shanghai (which kicked off this entire crazy chapter of my life), which I commemorated by listening to the indie rock album that served as my unofficial soundtrack during the cold, dark winter of 2009-10.

Which is not to say that every aspect of learning this lesson is sad. Certainly, arriving back in Beijing for the first time in more than six years, things were different from how they’d been in the most beautiful way.

As I waited to check in to my hotel in the city’s hip Gulou hutong district, staff asked me what kind of espresso drink I wanted and invited me to sit down. Inside my room, a platter of fresh fruit sat behind the pour-over apparatus I’d be able to use in the event that I wanted an additional complimentary cup of coffee. It was one of those hotels.

On the plate was xiang li, an Asian pear that was probably my most-purchased item at the South Shanghai Carrefour where I bought my groceries during the aforementioned cold, dark winter.

At Lama Temple later that afternoon, just after a few beams of sunlight had peeked through the Beijing smog long enough to make me think it might be clearing, a tap on my shoulder.

“Leave Your Daily Hell,” the young African-American man said, with an emotion that came off as somewhere between excitement and disbelief. “You’re Leave Your Daily Hell.”

I reached out my hand. “Yes, and also just Robert. What’s your name?”

After introducing himself, he explained how he’d used my blog to plan his recent trip to Taiwan, and that although he (like me, in the past) was living in Shanghai, this was his first non-business trip to Beijing. We didn’t chat long; I had a lot on my agenda, so I politely said goodbye to him sooner than I probably should’ve.

This never get old, I thought as he walked away, feeling thankful to have been recognized, given both how long I’ve been doing this, as well as the fact that I mostly shirk social media, which after all is where most fame originates in the 2020s.

As I made my way toward the Temple of Heaven in vain hopes that the sky would clear, I put Promise and the Monster back on. It was a throwback—and, if I even happened to lose perspective (or gratitude), a potential reminder.

“To fall,” the singer cooed over several more bars than two words should’ve taken up. “is the cure for vertigo.”