“You were breaking the law, yes,” she confirmed, and filled my cup with saffron tea. As the smell of steeping leaves and crocus stamens entered my nasal passage, I thought back on my sordid first morning in Iran.

Having woken at my usual 5 am, I’d ridden the Tehran Metro’s first train to the iconic Azadi Tower, which is apparently not as iconic among locals as it is among travelers.

“You’re photographing that?” A passer-by gawked, making neither eye contact nor explaining why she thought I was so foolish. As I made my way back toward the underground, a portrait of Ayatollah Khomeini glared down at me. I noticed that all the alleys along the road had names, and the dead ends did too.

Nasrin had seemed happy when I first met her in the drab breakfast room of Hotel Apadana, but her expression turned as sour as my orange juice when I told her of my adventure. Her words were innocuous but spoken piercingly, as if she were using the carrot jam on her stale flatbread to pop the balloon floating in the corner.

“Just tell me next time,” she smiled and poured me more tea. “I don’t want you to get deported.”

Of course, the fact that I simply needed to be with a tour guide everywhere I went in Iran was tame: Donald Trump has repeatedly tried to bar Iranians from entering the United States outright.

I’d been at Chicago’s O’Hare Airport, on my way back to Texas from Russia, when news of the first Muslim Ban broke. Anticipating that Iran would reciprocate, I knew my planned April arrival in Tehran wasn’t going to happen—in fact, I feared I would never make it to Iran. Thankfully, the company that arranged my trip was unrelenting, and in late August the application they’d submitted in early June was finally approved.

It was the afternoon of October 2 when I first laid eyes on my country’s former embassy, its walls emblazoned with the phrase “Down With USA,” and some visual anti-American messages as well. As my taxi sped past, I wondered if we’d ever have diplomatic relations with Iran again—and, more pressingly, whether there was still a way to avert the long-prophesized war. The sky strobed from orange to blue to purple as I move away from the setting sun, and I arrived at the so-called “Roof of Tehran” just as night had fallen.

There, I made the acquaintance of a woman named Maryam, who insisted her children guide me to their city’s most famous viewpoint.

The kids had spent the previous few summers seeing family in London (and, prior to 2016 election, Washington), Mom explained, and needed to speak English as often as possible when at home to avoid losing their fluency. She expressed her condolences about the previous day’s shooting in Las Vegas, and I laughed as I told her how many of my friends and family were more worried about my safety than their own.

“You’ll be safe as long as no one who knows the rules finds you,” she scolded me lightly, pulling her drooping scarf only about halfway over her hair. “Most don’t, of course. The only reason I know is that a friend of ours from DC came a few weeks ago, and she was practically barricaded inside her hotel room.”

The Iranian capital sparkled before us like a carpet of stars, the smell of marijuana smoke and the sound of teenagers making out filling the air—we could’ve been in Austin or Amsterdam or even Las Vegas, without the threat of machine gun fire. You can always depend on the kindness of strangers, even in Iran—especially in Iran.

After Tehran I headed to Kashan, a city famed for its historical houses, city walls and ancient bazaar. But what stuck most with me about my time there was a young girl I saw playing in the bay window of a school. Covered in a chador despite the fact that she was only six or seven, she gazed at me with an optimism that was piercing, not unlike Nasrin’s words had been at breakfast days earlier.

I hope she knows better than me, I smiled back, even though I was worried inside. Blood-red light bathed the nearest pair of minarets.

Natanz, to be sure, boasts even fewer obvious attractions than Kashan. Two, to be precise: The 14th-century Shiekh Abdol Samad Mosque in its center; and a nuclear facility, at least according to a decade of report from Israel’s Haaretz newspaper. It was in front of said mosque that I came across Ali and Hamid, a pair of extremely attractive brothers who were selling saffron products to passing tourists.

As Ali showed me pictures from a recent sojourn to the family’s farm, I noticed Hamid’s pectoral muscles bulging through his bootleged Stranger Things t-shirt out in my peripheral vision. The rolling fields of purple crocuses were beautiful, but they were no match for Hamid, who was among the more attractive young Iranian men I’d seen. And that’s saying something—they’re all studs.

Indeed, I’ve never felt more inclined to have gay sex than I did in Iran, in spite of knowing how harsh the punishments are for it—if you get caught. I mean, I probably could’ve deflowered one (or both) brothers in the nearby rose garden, and the elders bumbling about the town center would be none the wiser.

Or maybe one would, and I’d be pushed off the roof of the mosque and meet my end on the table where they were Ali and Hamid their products. Perhaps my country’s military would drop a bomb into the rose garden and we’d all be dead, regardless of who we wanted to sleep with or whether centrifuges were actually spinning, all the turquoise tiles pulverized into powder.

It was Wednesday when I met Kourosh, a teenage Eminem fan who views the Islamic Revolution as a capitulation of Persian culture to Arabs. He’d approached me in Isfahan’s Naqsh-e Jahan Square, which dates back to the early 17th century Safavid period—ironically, when Shia Islam became the official religion of the Persian Empire.

He admires girls his age, he said, who push the boundaries of both the hijab and the modesty of fashion in Iran in general, and was wearing white that day—and every Wednesday—in solidarity with them.

Azar, on the other hand, runs a fancy espresso bar on the edge of the Mesr Desert with her husband Farhad. On Saturday afternoon, just before sunset, she reminisced about the three years they spent living in Canada, and told me dozens of stories of their time there. He said he regretted never having traveled over the water to Detroit, and chuckled when I told him he hadn’t missed much.

As they said goodbye to me on Sunday evening, they gifted me with a small ceramic bowl I’d been eyeing —accompanied, of course, by one last americano.

Days and deserts separated these conversations, but they blend together as I imagine them now, like sands from two continents meeting over the sea.

“We have no freedom in this country,” Kourosh had confided in me as we slurped saffron soft serve together, “I wish I could emigrate to yours.” Azar, in a similar vein, was surprised that someone from a place like America would even want to visit Iran, while Farhad feared that Trump would find a way to re-impose sanctions, stunting the economic growth that had been his only motivation for not seeking residence in the States.

“Ironic, isn’t it?” he wiped off his milk steamer, going on to concede that he understood why certain governments had reservations about his. “Rouhani is wonderful,” he explained. “But he’s not the one with the real power.”

Kourosh and Azar and Farhad, and almost every other Iranian I spoke with during my trip, told essentially the same story: Iranian people share largely the same worldview as the West, and would like to see their country evolve accordingly. That leaders—one in particular—would want to antagonize such natural allies in the fight against extremism was troubling, but unsurprising.

I arrived in Yazd, by some accounts the world’s oldest continuously inhabited city, the following Tuesday. In a few days, the Donald would certify whether Iran was in compliance with what he’d previously called “The Worst Deal of all Time.”

Yet Iranians continued to smother me with adoration after learning I was American, sometimes to an absurd extent. One man gave me a sloppy kiss on the lips as I was leaving lunch, while a group of older woman asked me to pose for nearly a dozen photos with them at the base of the Tower of Silence.

Maybe it’s the legacy of Zoroastrianism, I postulated as I looked down onto the city from the edifice where hawks had eaten the flesh of countless Yazd dwellers during the pre-Islamic era.

Ascending to the rooftop of Charisma restaurant just after sunset, the dome and minarets of Jameh Mosque glowing blue in the darkening sky, a member of my tour group broke with our tradition of sticking to pedestrian conversation topics, and asked Nasrin about gay rights in the Islamic Republic.

My heart sank—in spite of all the homoerotic thoughts I’d had, I was as petrified to publicly acknowledge gays in Iran as Ahmadinejad had been 10 years before.

It sank deeper when she began to speak. “They don’t exist here,” she, too, echoed the man many Iranians now refer to as their Trump. “And if they did, they’d be punished in the harshest means possible.”

I imagined my body thudding against the floor of the square, and wondered if the people who’d showered me with love during the previous two weeks would cheer as I took my last breath.

If sight had been my only sense as I sat inside Shiraz’s so-called Pink Mosque on Thursday morning, I would’ve felt as serene as I look in the pictures of me sitting there. Yet years of social media fame have turned the holy place, which had been otherwise anonymous since its construction by the Qajar dynasty in 1888, into a spectacle more chaotic than any bazaar I visited in Iran.

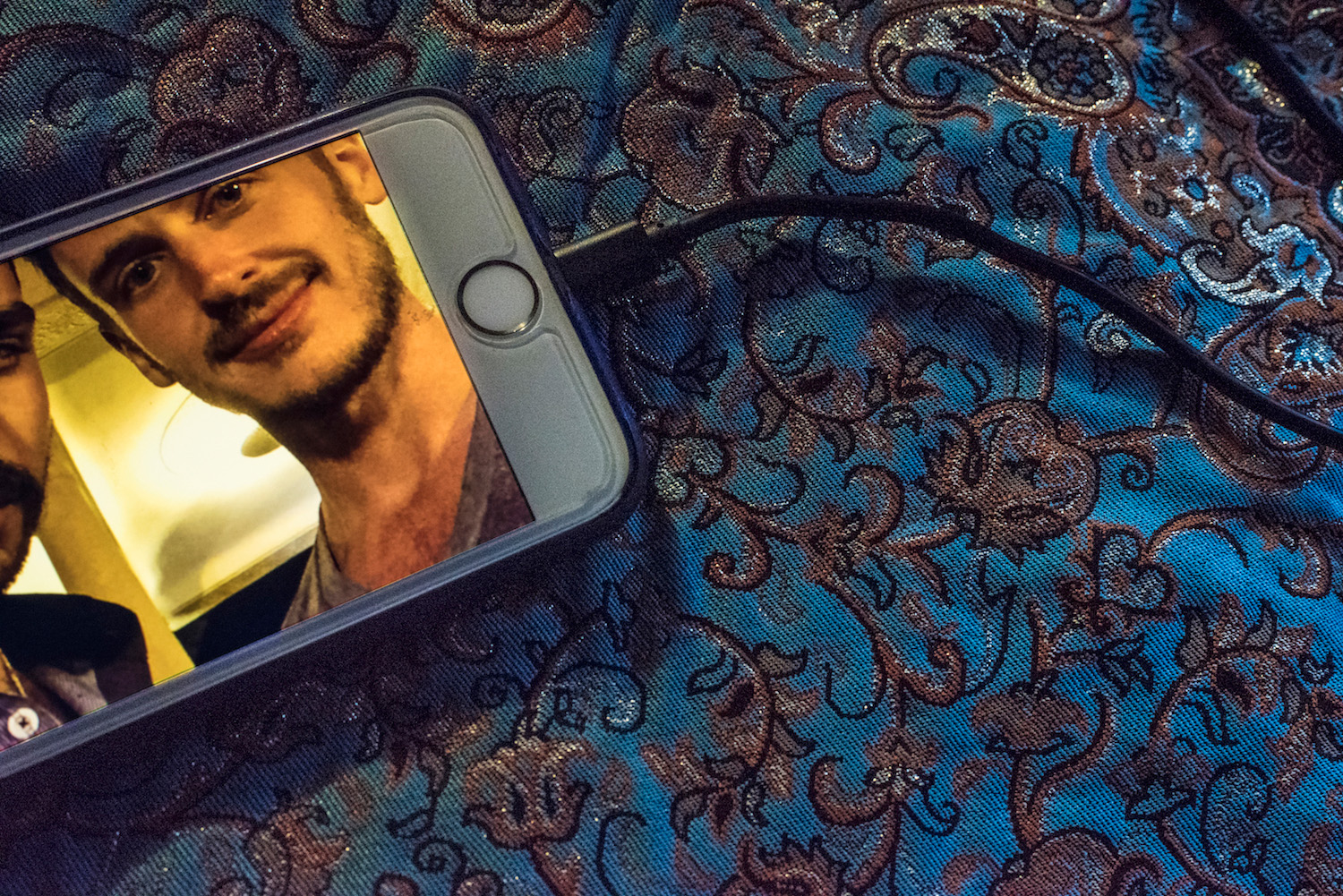

But you enjoyed it? The words on his screen read. Felix spoke as little English as I did Farsi (he only got as far as telling me he had a “Roman” name before deferring to his smartphone), so we communicated via the Google Translate app.

I couldn’t hold him close as we counted the headlights on the highway below us, but when the staff wasn’t looking, he’d grab my hand as if to ask for a tiny dance. I’d swat him away the moment someone directed his gaze back at us, and although I knew he knew it was for our protection, I felt guilty doing it. But when he kissed me at Hafez Tomb, where locals were celebrating the birthday of the legendary Persian poet, I let him.

I replayed our evening together in my heart as I returned to the burial site the next morning with my tour group. Nasrin read aloud the fortune a man with a parakeet had sold to me for 10,000 rials—composed, naturally, using the words of the Shirazi bard himself.

“You don’t usually care about the Universe,” she said, though I wasn’t sure if she was paraphrasing or translating verbatim. “But your perspective has recently changed.”

I noticed that some fuchsia Four O’ Clocks were blooming, and found it odd given the hour of the day. A man sitting on a nearby bench was wearing a shirt that said “Freedom Has a Cost,” which looked like it had been sold at Walmart during the George W. Bush years, and reminded me of Bill O’Reilly’s recent Vegas commentary.

And Felix, for his part, is a dead ringer for my ex Danilo, but the sum of these individual observations was nothing short of celestial—the questions being raised on my trip were bigger than serendipity or sonder.

Why was the gulf between most Iranians’ mainstream world views and their medieval perspective on gays so vast? (“My biggest dream in life in to seek asylum in Turkey,” Felix had confessed to me when we said goodbye the night before, begging me not to leave him as he told me of all the harassment and violence he endures on a regular basis.)

Then there was the ill-chosen leader of the free world, and his forthcoming announcement. Did he really want to see every person in Iran reduced to stardust?

The answer wasn’t surprising—Trump de-certified the so-called Nuclear Deal as expected—but it was ambiguous: He would leave the decision of whether to punish Iran up to congress. And I still found it alarming even though Hassan, a friend of Nasrin’s who’d invited our group to his home for a goodbye dinner, brushed it off entirely.

“Please eat,” he insisted, and put on a video of himself dancing at a friend’s wedding party. His joy was palpable, even when consumed in compressed pixels. It was no wonder he could so easily disregard the year’s most devastating development, let alone still be hungry enough to partake in the feast before us.

In Iran, Four O’Clocks bloom in the morning, dead ends have names and poets’ birthdays are national holidays. Gays exist here, women abhor the chador, teenagers make out and get high (at least in Tehran) and people worship Americans as they chant “Death to America.” It’s more Islamic than it is a Republic, but it’s not a terrorist state by any means.

The two weeks I spent in Iran informed me and changed me and humbled me, and I ask all of you reading this to humble yourselves.

To my fellow Americans, I hope you will follow in my footsteps, even though the visa process is tedious, and even though we’ve been told for the better part of four decades that Iranians are our enemies. If you can’t or won’t visit Iran, please listen more than you speak.

To Donald Trump and Congress, please expand your thinking on the so-called “Iran issue.” There are legitimate grievances to have with Iran’s government, but people here are mostly on the same page as we are. I wish you could see the joyful way they dance.

To the Iranian government, end your extremism. Stop pushing gays off buildings and forcing women to cover, and if you are building nukes or funding terror, knock those off as well. Give moderates like Rouhani and Zarif as large a voice in policy as they have in PR.

To the people of Iran, I thank you for your kindness, for your questions, for your kisses and for your food. Please look after all the new friends I left behind. Especially Felix, so that he doesn’t have to run away to find the happiness he deserves.

None of us are illegal, and we all deserve the happiness we seek, and although my voice isn’t loud or powerful, I hope it helps move the needle at least the width of a strand of saffron.