“If you plan to get off at Shimoyoshida,” a pre-recorded announcement blared through the station as the doors to a spartan local train creaked open, “make sure to board cars one through three.”

Few of the tourists who subsequently congealed into the carriages seemed to pay the notice any mind. For me, however, it felt existential.

As we began crawling westward from Otsuki, which is about halfway between Tokyo and the Fuji Five Lakes region, I thought back to the first day of my trip.

It had started under similar circumstances: I was making a mad dash; I was also wholly dependent upon all the slowest remaining forms of transport in Japan.

The madness of my method, if not my thwarted dash, had paid off. I arrived to the Urui River, which flows through Shizuoka prefecture just south of Mt. Fuji, to find the iconic peak completely exposed under the perfectly clear sky. All the cherry blossoms running along the river’s banks were at perfectly full bloom; having ticked one of the top items off my list right out the gate, I’d begun this particular sojourn on the literal best note possible.

The question, of course, was whether an ending as impeccable would await me after disembarking in Shimoyoshida.

The answer did not seem to be yes. A thick quilt of clouds hung over the inaka outside the slow-moving densha, casting a pall over the fact that most of the cherry trees dotting the pastoral scenery had reached mankai. It hung low, too, resting atop the ridges that rose above the rice fields and cemeteries (which, eerily, seemed to outnumber homes for the living in many instances) like a slice of sashimi on a slab of vinegared sushi rice.

It was somewhat coincidental—a quirk of the way the so-called “cherry blossom front” moves—that I would find myself near the base of Japan’s famous (and infamously shy) mountain for the second time in just a few days.

After saying sayōnara to Urui-gawa that Thursday morning, I’d boarded a westbound Shinkansen for my former, adopted furusato of Kyoto, where the conditions for hanami were similarly perfect. As I strolled later through evening along Gion’s Hanamikoji-dori, which was so crowded that tourists couldn’t chase Geisha down narrow yokocho even though they desperately wanted to, I felt strangely gratified.

Actually, it wasn’t strange at all. Japan’s pandemic-era border closure, which was among the longest and harshest in the world, had nearly destroyed my business. Prior to covid-19, you see, the website that started as a niche side project had quickly approached and eventuality eclipsed this one in terms of both popularity and profitability.

The longer Japan stayed closed, especially as evidence continued to mount that doing so offered little health benefit, the more I felt the years I’d spent exploring the country in order to gain the expertise that had given me such an edge might’ve been wasted. I became bitter and spiteful, and one more than one occasion pondered throwing in the towel

As night fell in earnest, I crossed the Sanjo Ohashi bridge over the Kamo River and strolled back to my hotel via Kiyamachi-dori. I quickly lost count of how many smiling, laughing faces I saw peering through the cherry blossom billows that frame the windows of the street’s izakaya pubs and obanzai restaurants, all of which were full to capacity.

With each moment of joy I observed that night, I’d felt my bitterness fall away ever-so-slowly, like the way sakura flowers shed their petals one-by-one. I tried to re-manifest this intention as the densha continued pushing westward ever-so-slowly days later, Fujisan‘s status just over the ridge still unknown.

Like everywhere else I visited back then, Miyajima island was in full bloom during my first Japan trip, although the sakura had mostly been an afterthought: I was there to see the famous “floating” torii.

Whether it was because of my success in this regard or because of the gate’s years-long reservation that began shortly thereafter, I no longer remember. But I didn’t bother returning to Miyajima until last year’s autumn season and, while enjoying the superlative yellows and reds, realized the island was also low-key a first-first hanami destination.

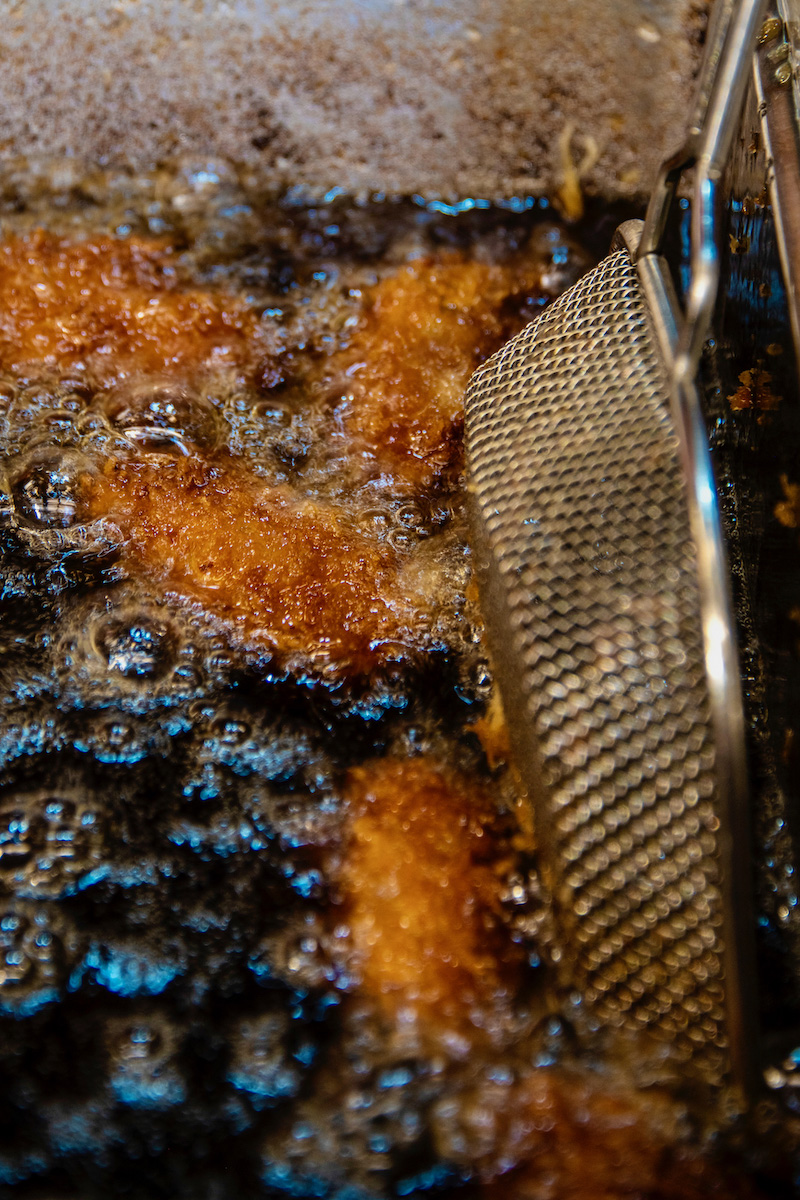

It’s also Japan’s most underrated destination for street food (and drinks). This time, as I waited for the sun to set such that pictures of the gate from Taho-to (which was itself now under renovation) wouldn’t be washed out, I took advantage of one street bar’s generous ¥100 refills on its yuzu highballs, an oil-soaked tray of fried oysters in my other hand.

Just as I’m ambiguous, looking back, as to why I chose not to come back to Miyajima for more than eight years, I can’t say for sure why my ankle bent into a perfect right angle as I walking down cobbled stairs from the pagoda. Was it because I was slightly drunk, or because I’m 38 and was paying more attention to deer frolicking under falling petals than I was the path ahead of me?

What I can say—and this is definitely because of how stubborn I’ve become in my nearly four decades on this planet—is that I wasn’t about to let a low-grade injury stop me, even for a second. The days ahead were too important: This was so much more than sightseeing.

I had a slight limp, to be sure, as I headed back to the ferry port after sunset that evening. It persisted the next day, as I traipsed around the ruins of a castle that had once stood in Toyama prefecture’s Takaoka, a city I decided I want to visit after passing through it once upon a time, but that didn’t especially live up to the hype I’d created around it when I finally came back.

If I’m honest, my stride was still slightly tentative even that morning in Otsuki, to the extent that I waited until the clot of tourists had fully congealed to enter the carriage, even though I knew that would mean me having to stand for the entire journey.

The possibility of a chronic injury was but one of anxieties I continued to suppress as, to my shock and amazement, Fujisan showed itself once the train rounded a particular bend, towering into a perfectly blue sky without so much as a single perceptible tuft of condensation obscuring its glory.

It would be too dramatic to say that it felt miraculous—the mountain is introverted, not imaginary—but certainly, the thick quilt of sashimi clouds seemed to have left some magic in its wake.

I’d last walked up the 400 steps to Churei-toin 2021, when I’d managed to enter Japan on a student visa literally days before it slammed its border shut for the second time in a year. Then, in addition to the sakura being at least a day or two past their prime (2021’s season was the earliest in over 1,000 years), there had been no sign of Mt. Fuji, which on that day might as well have been mythical.

In a tangible sense, this wasn’t serious. Every year, millions of tourists fail to see Fuji in spite of their best efforts; even fewer are lucky enough to catch a glimpse during cherry blossom season when the trees have reached an impeccable state of mankai.

For me, however, having achieved the insurmountable task of breaching Japan’s proverbial during its second sakoku period, it was nothing short of tragedy. It sounds ridiculous to say now but, at that time, the notion of Japan ever opening to general travelers again was impossible to imagine, to say nothing of how unsure I was that I’d be able to hold on financially even if it did.

To be sure, while I had legitimately wanted to learn (and did learn) Japanese during the six months I ended up spending in the country that year, I had secondarily expatriated myself to completely all the travel I’d had planned for 2020.

The idea was that if Japan were to open before I exhausted my resources and abandoned ship, I’d be able to move forward more or less as if the pandemic had never happened, instead of having to wallow in the past as the world moved into the future without me.

As I not-so-slowly made my way up the 400 steps—I was moving faster than the train had done, I reckon—I wasn’t just on the cusp of getting what is probably my favorite shot (if not the most original one) I’ve ever snapped in Japan.

No, as the voluptuous pink and white tufts swayed almost imperceptibly in wind that was barely blowing—time was standing still, leaving space to twiddle its thumbs alone—and Fujisan remained impervious to the notion that clouds exist at all, I was slaying a demon. I was taking back what was mine.

I had survived—and this picture was my proof of life.

Descending from the viewpoint, but not yet having come down from my high, I noticed a man around my own age (which is young, for Japan) out of the corner of my eye.

Standing behind a white table with around a dozen beer bottles lined up atop it, he was maskless (which is strange, for Japan) and seemed eager, albeit not enough to engage me in conversation as I walked by. Still, after getting a look at the mountain through the shrine’s lower torii, I went back and introduced myself.

The decision paid off. Although his English was as tentative as my own Japanese, I was able to divine an abridged version of his life story, which was surprisingly similar to my own.

Like me, he had grown up in a family that moved often for his father’s career; he had also left home at 18 and, after hopping around his country, expatriated himself (in his case, to Italy), where he found both fortune and wisdom before returning to Japan amid (but not because of) the pandemic.

Like me, he had lived many lives in his 38 years. Some were fleeting—working as a chef in Tuscany—while others were recurring, like his near-annual participation in the Yabusame Matsuri horseback archery festival in nearby Fujiyoshida.

As he popped the top off a bottle I eventually ordered in spite of not being a beer drinker, he described becoming so proficient at what was supposed to have been a part-time beer pub gig in Kobe that he eventually competed in Stella Artois’ world championship at Asia’s top tapmaster.

And he decried having often become listless in the interstices between his triumphs, and fearful that they might one day slow to a trickle or stop entirely.

“But now,” he concluded, “very recently, in fact, I feel as if I am back to where I would’ve been, if ko-ro-na didn’t exist.” A breeze wafted the subtle perfume of the park’s hundreds of cherry blossom trees through the crisp air. He didn’t elaborate on his coda, at least not verbally.

Vanquishing the ghosts of the past is simply a matter of surviving—eventually, the weight of the present will no longer crush you.