As I walked down the hall of the hotel, with its brown carpet and plastered faux-finish wallpaper, a Muzak version of “Don’t Cry for Me, Argentina” began to play. I pressed the button, and the elevator arrived the moment Evita would’ve stepped onto the balcony, had this rendition of the song not been a cheap imitation.

Descending, I looked into the golden door, attempting to assess my hair, but the diamond shapes frosted onto it left too little mirrored surface for me to verify my own identity, let alone the integrity of my slept-on mane.

Arriving at the ground floor, I caught a glimpse of the sun rising through palm trees just outside the lobby doors, and a gust of the freezing wind that belied their sway. The taxi that drove up was numbered 2294—both today (2/2) and the birthdate of my long-dead dog (2/2/94).

If Hotel Clement had been located anywhere else in the world, I would’ve found it cheap and tacky. But 1980s architecture in Japan, particularly 1980s Japanese architecture I can step inside, always makes me think of the decidedly timeless characters Haruki Murakami creates within decidedly 1980s worlds.

To be sure, I was only about 200 pages into the behemoth 1Q84 by the time my bus sped past cab #2294—I didn’t yet understand Tengo or Aomame, its two main characters.

But I could imagine either of them walking down the brown-carpeted, faux-finished halfway, although in their world’s version of the hotel, Muzak wold be replaced by a piece of classical music, almost certainly Janáček’s “Sinfonietta.”

Shikoku’s most famous attraction, Naruto Whirlpool, isn’t so much a whirlpool as a bizarre confluence of ocean currents that very occasionally creates whirlpool-looking disturbances in the water.

This fact proved both to be both a disappointment and a relief: Had a single, persistent whirlpool existed under the Kobe-Awaji-Naruto Expressway, the boat I was on certainly would’ve been sucked into it.

Disappointing and relieving—and predictive. My first full day in Shikoku fixated on sights whose peripheries were more interesting than their cores: Hotel Clement because of my obsession with Murakami and 1980s Japan; an Awa Odori dance performance where the dancers invited guests on stage; a strawberry-growings greenhouse brightened by bossa nova covers of Rihanna’s greatest hits.

At Ryozenji, a temple along the Shikoku pilgrimage route that’s only slightly less famous than Naruto Whirlpool, I noticed my memory card had 666 pictures left on it—Japan always makes me feel more superstitious than I am.

The onsen where I slept that night was mediocre, but maintains a steep funicular railway, which transports guests to a ravine-bottom hot spring. As a computerized voice informed me that I would soon be reaching the bottom, a well-performed version of Debussy’s “La fille aux cheveux de lin” began to play inside the car.

I used to listen to this after Penny died, I sighed, and grabbed my towel as I marched toward the water. Today is Penny’s birthday.

There is no need for the one in the center of a whirlpool to move. That is what those around the edge must do.

-Haruki Murakami, 1Q84

1Q84 is a behemoth book (just under 1,200 pages), but I thought I’d figured it out when I was a mere 300 or so in—my third day in Shikoku.

As the book begins, we walk in on a young woman named Aomame killing a man in his hotel room. Her chapters alternate with those of Tengo, a young man who aspires to create his own fiction, but has been hired to re-write Air Chrysalis, a mysterious book written by an equally mysterious girl named Fuka-Eri.

Slowly, we learn why Aomame has come to make her living as a killer: Tangibly, to help settle the score for an old dowager she met and became close with; esoterically, to avenge the childhood abuse she suffered at the hands of a religious cult. Tengo, meanwhile, meets and becomes close with Fuka-Eri, which threatens to defeat his mission: The public is to believe that Air Chrysalis is Fuka-Eri’s alone.

A third of the way into 1Q84, certain symbols from Tengo’s novel begin to appear in Aomame’s real life—the so-called “Little People”; and a second moon in the sky. But it isn’t until Aomame speaks eight particular words—”Where I’m living is not a storybook world”—that I first conjectured she might in fact be living inside a storybook.

I peered out my window toward the ravine, now illuminated by the morning light.

It was only a short journey from the mediocre onsen to the mountain town of Oboke, where an old woman in a backwards skater hat abandoned her tofu shop to escort me around, as if she had nothing better to do.

“Are those red things carrots?” I asked her.

“Oui,” she answered in French, apparently not able to speak English, but aware that I could see her eating some sort of raw-egg concoction. “Les oeufs japonaises n’ont pas de bacterie.”

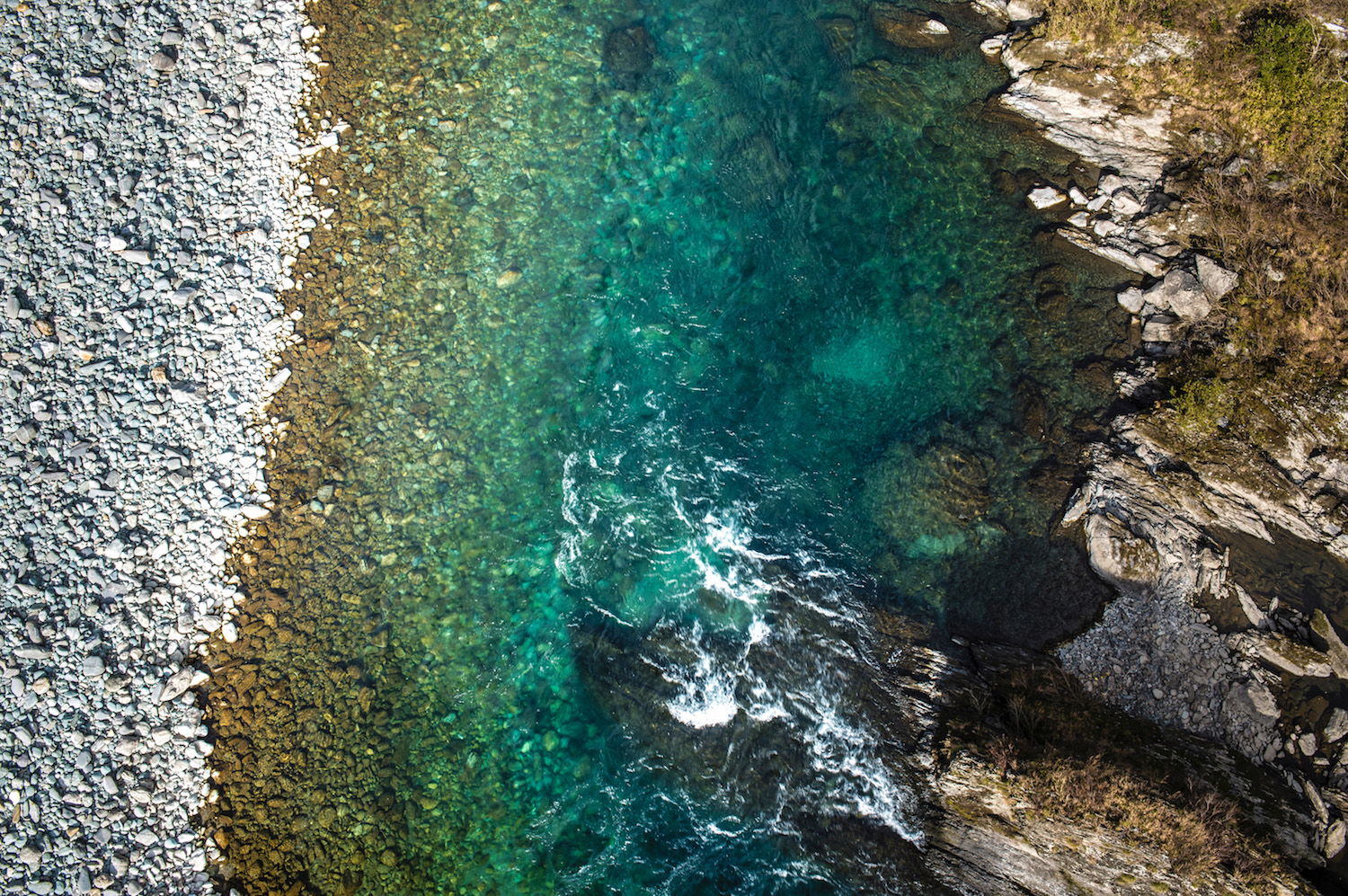

We walked out over the blue waters of the Yoshino River, and I wondered to myself as I looked at the rocky bed whether the red carrots in my story were like the two moons in Aomame’s. Maybe I am living in a storybook world.

Otherwise, I conjectured, Japanese eggs would be just as prone to bacterial infections as eggs laid elsewhere.

Everyone, deep in their hearts, is waiting for the end of the world to come.

I was inside a 7-11 in the city of Kochi when the message appeared on my phone. It was Ahmed, a longtime reader of my blog who’d sort of become my friend, and as I heard the ding, an instrumental version of the Monkees’ “Daydream Believer” came onto the loudspeaker.

“Aren’t you afraid of tsunamis,” he asked, without a question mark.

If I’m honest, I thought but didn’t say, I’m terrified.

During my first trip to Japan three years earlier, while waiting in line at Tokyo’s Tsukiji Fish Market, I’d met some Americans who were living in Shikoku, who told me it was the most tsunami prone part of Japan. I never verified this independently, but I still believe it.

As I began walking toward Godaisan pagoda, I became curious about the red hats the buddhas were wearing. They reminded me of how I haven’t spoken to my mother since our post-Christmas feud and how I imagine her crocheting in order to make myself feel less guilty.

“The hats honor the spirits of miscarried babies,” one of the volunteer guides explained to me. “Isn’t that touching?”

That afternoon, I found myself once again over a crystalline Shikoku river, this one the Shimanto. A sign explained how the bridge I walked upon would be completely submerged during heavy rains, or “other high-water circumstances.”

Like the tsunamis Ahmed mentioned, I thought, realizing I hadn’t yet responded to him. Everyone, deep in their hearts, is waiting for the end of the world to come.

It seemed both futile and fitting to associate the scenery here with Armageddon: It was a trifecta of the purest sort—opalescent sky, emerald forests and a sapphire stream.

“But signs of higher water are everywhere,” the sign continued, noting the various spots on the shore where bamboo rods had fallen onto one another like Pick-Up Sticks.

Robbing people of their actual history is the same as robbing them of part of themselves. It’s a crime.

The term “1Q84” appears relatively early in the book, just after Aomame spots the two moons above her. Her life, she believes, “switched tracks” from 1984 to a different world, which she terms “1Q84.” She subsequently learns that the Little People create alternate versions of people (A “dohta” to the original “maza”) inside their air chrysalises, which seems to corroborate this.

We then learn that she and Tengo actually knew one another a couple decades before. They still frequently think of one another, and ultimately desire to meet. By the time I’m halfway through the book, however, I’m still imagining this is all a function of Tengo’s having written an imagined version of Aomame into being—she’s just killed the leader of the cult she’d once been a member of, which Fuka-Eri conveniently lambasts in Air Chrysalis.

I switched tracks, too. I’d accidentally boarded the inland Matsuyama-bound train, so I canceled my previously held plans to head directly to Dogo Onsen, and instead went up the ropeway to the city’s castle to end my fourth day in Shikoku—I needed to see the ocean again.

There, as the setting sun painted the lower reaches of the sky the same orange as the crispy river prawns I’d eaten for lunch that day, I saw half a dozen young children skipping past.

Japan isn’t a dying country after all, I breathed a sigh of relief.

The next morning, I found myself once again in a 7-11 in a city most people have never heard of, ignoring Facebook messages from a reader-turned-friend, and humming along to an instrumental version of a song from years gone by, this one The Bangles’ “Manic Monday.”

Of course, I laughed and took a sip of my Red Bull, I don’t need to wish it was Sunday—it is Sunday. On Monday, I go back home.

Before mid-day, I’d traipsed through Takamatsu‘s Ritsurin Garden in a downpour. By the time the sun set behind the mist the rain left in its wake, I’d climbed 1,368 steps to the top of Konpira Shrine.

I remember standing there at the peak, a thick fog surrounding me like a whirlpool of clouds, and hearing my name whisper-shouted, as if someone with emphysema was calling out for their morphine.

Time flows in strange ways on Sundays, and sights become mysteriously distorted.

Monday started with a gale, which blew in a blue sky. On my descent from Marugame Castle, which I’d skipped the previous day on account of the weather, I saw a man wearing a “Don’t Mess With Texas” hat.

“I’m from Texas,” I told him, assuming he wouldn’t understand English well enough to appreciate my full Lone Star story. (I’d been born in the state and raised by a full-blooded Texan mother; and I’d subsequently moved back without her, which cost me a portion of the relationship we once shared.)

As I rambled toward the center of Marugame, now able to see the end of my strange trip to Shikoku in my mind’s eye, I could hear the melody of “Manic Monday” once again.

I’ve never been a museum person, but certain elements of certain ones lasso me. In the case of Marugame’s Genichiro Inokuma Museum of Contemporary Art, it was Inokuma’s painting Windows and Constellation.

A few things took me aback when I saw this picture, first off that it was painted the year I was born. The title of the painting reminded me of the moment Aomame looked off the balcony of the place where she was hiding and saw Tengo atop a playground slide: They’d both been looking up at a sky with two moons hanging in it.

You see, although I’d assumed almost until the end of 1Q84 that my prediction about the book being a story-within-a-story would prove correct, Tengo and Aomame really did become star…er, moon-crossed lovers.

Actually, it’s more complicated than that: Near the end of the book, they both acknowledge they’re trapped in 1Q84 (which Tengo has come to refer to as the “cat town”) and, hand-in-hand, find a way into a third, stranger reality. Also, Aomame is pregnant with Tengo’s child: The Little People used Fuka-Eri’s body as a conduit when Tengo slept with the underage girl one stormy night—an Orwellian treatment of the immaculate conception.

I wonder what Mom was doing in 1984? I stared up at the painting, realizing its blue was the same color as my blazer. The year she conceived me.

She’s become a cat lady in her later days, so instead of getting her a print of “Windows and Constellation” to remind her of my birthday, I bought “Dreams of Ballerina”: A smiling, sleeping woman surrounded by more cats than she can count.

Many of my nightmares center around missing planes, so it might be shocking to learn that an hour before my flight from Tokyo-Haneda to Los Angeles began boarding, I was inside the observation deck of the Tokyo World Trade Center, camera atop my tripod, watching the sun set behind Mt. Fuji and the city’s skyline.

I ended up making it on time—right on time: The moment I reclined in seat 7A at the back, left corner of the business class cabin, I noticed a familiar face beneath familiar blonde hair.

“I’ve flown with you before,” I tapped her on the shoulder, not remembering her name. “On the LAX to Narita flight, back in October.”

As she started back at me, clearly not as taken by our chance encounter as I was, I remembered a sentiment Murakami had expressed through one of the peripheral characters in 1Q84: “The world survived the Nazis, the atomic bomb and modern music.”

When I first met her, we all thought Hillary Clinton would become President; we still don’t know if Donald Trump is as survivable as Hitler, Hiroshima or Rihanna’s hits, without the charming kitsch the Japanese impart upon them.

We’d been on the same flight, after all, in 2016, which had shortly thereafter become a 2Q16 of sorts, so it makes sense that it took her a minute—a full minute, I think—to remember this strange person sitting in 7A in 2Q17, or whatever alternate version of 2017 we currently find ourselves in.

“Sorry,” she apologized and smiled, putting her hand on my shoulder. “I just finished making the beds in the back—all five of them; we take rest five at a time. Have you ever made five beds at once?”

I shook my head. “I try not to make any beds, if I can.”

As she described the complicated process of trying to prepare the quintet of sleeping pods in assembly-line fashion, I imagined her making an air chrysalis: Weaving invisible threads into something visible.

I tried to listen intently as she went on talking, but found myself consumed by speculation. Were we our dohtas, or our mazas? Did my mother once speak about me in the devastated, yet relieved way this woman spoke about her own almost-adult son? Did the past switch tracks alongside the present—was the Penny I now remember born in 1994, or 1Q94?

Am I at the center of the whirlpool, I thought, as I noticed her name for the first time, or around its edges? Margaret, like the river in Australia I’ve never seen. Australia, the country the President is going to blow up if they send us any more refugees.

We are being drawn into a great whirlpool. It may be a lethal whirlpool, but violence creates certain kinds of pure relationships.